The topic of synthetic opioids has long begun to worry me, but the other day I came across an article that reveals more data on the actual state of things in the United States. Sadly, this country is the locomotive of the world not only in positive aspects, but also in some disturbing and negative ones. In this case, other countries and communities have a clear example and valuable experience in order to build their own way.

Below you will find my free retelling of a great article Fact vs. fiction: naloxone in the treatment of opioid-induced respiratory depression in the current era of synthetic opioids. All graphs and tables are also taken from this article, unless otherwise specified.

Opioid Epidemic Today

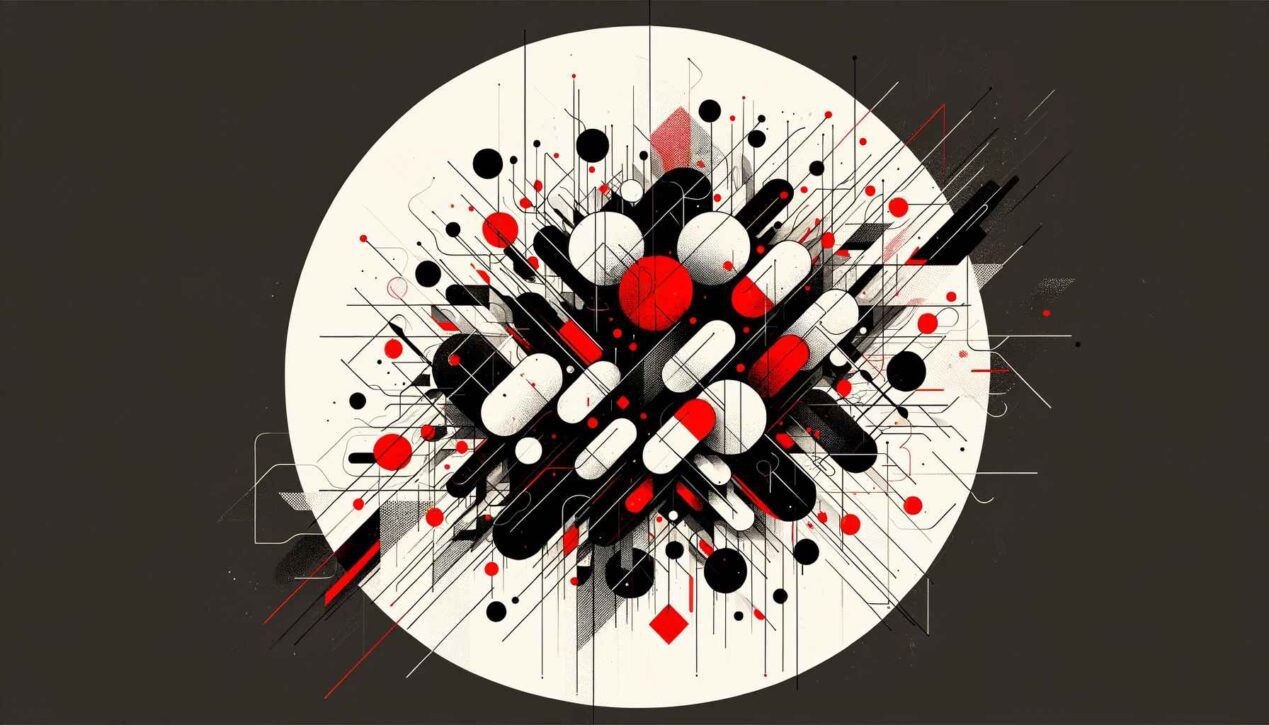

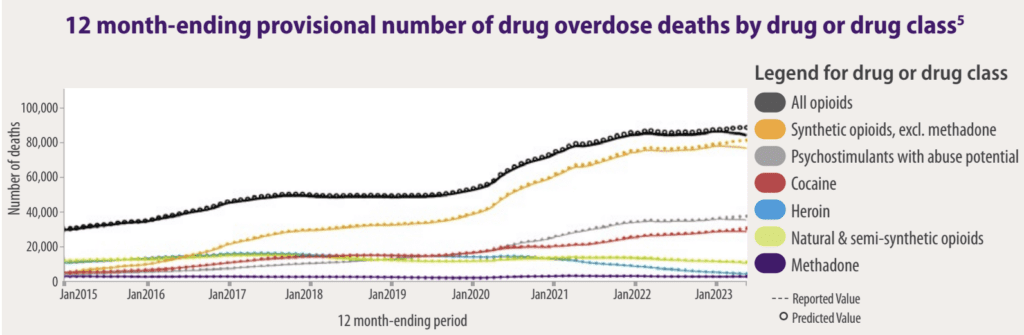

In 2022, approximately 80,000 people in the US died from opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD), accounting for about three-quarters of all drug overdose fatalities. This number has skyrocketed by around 400% over the last ten years, primarily due to the sharp rise in the use of synthetic opioids like fentanyl and its more potent relatives, such as carfentanil. For context, fentanyl is about 224 times more potent than morphine, significantly increasing the risk of respiratory failure and deadly hypoxia.

Opioid-related deaths typically involve individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD), but they can also tragically affect those without OUD who are prescribed opioids. Especially vulnerable are those prescribed high daily doses (over 50 morphine milligram equivalents), or those combining opioids with other substances like benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, or alcohol. Such people may overdose accidentally due to errors like misinterpreting dosage instructions, self-medicating for additional symptoms, or confusion from age-related cognitive changes.

Demographically, opioid overdose rates are higher among men compared to women across all age and ethnic groups. Additionally, those who are male, younger, white, and born in the US are at a higher risk of suffering from OIRD.

The Legacy of Morphine

In recent years, synthetic opioids have become the primary culprits in opioid-related deaths. By 2021, around 90% of all OIRD fatalities were linked to synthetic opioids. During the period from 2016 to 2021, the overdose death rates from fentanyl alone soared by 279%, climbing from 5.7 per 100,000 to 21.6 per 100,000.

In terms of potency, which reflects the amount of a drug needed to produce a specific effect, fentanyl is about 224 times more potent than morphine and 30-50 times more potent than heroin. Carfentanil, an extremely potent variant, surpasses morphine’s potency by a staggering 10,000 times. It’s crucial to distinguish between potency, which refers to the concentration of a drug required to achieve 50% of its maximum effect (EC50), and efficacy, which is the maximum effect a drug can produce. Beyond a certain point, increasing the dose of a drug will not intensify its effects, which defines its efficacy.

Fentanyl Death Star

Fentanyl, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), is widely used in medical settings to manage pain in cancer patients and to provide anesthesia and perioperative analgesia in other clinical scenarios. However, the majority of opioid-induced respiratory depression deaths involving fentanyl in the US are linked to its illicit production rather than misuse of prescribed medications.

Fentanyl is not only cheaper but also easier to synthesize compared to heroin. For instance, the wholesale cost of heroin was around $60,000 per kilogram in 2017, whereas fentanyl cost significantly less at approximately $3,500 per kilogram. Its high potency allows it to be easily concealed and transported, which lowers the risks for those involved in its illegal distribution.

Fentanyl is often sold as counterfeit opioid pain pills that mimic the appearance of medications such as oxycodone, oxycodone/acetaminophen, or hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets. A grave risk emerges when fentanyl is clandestinely added to stimulants like cocaine or methamphetamine, significantly increasing the danger of OIRD among users who are typically opioid-naive and at a high risk of overdose and death.

US Customs and Border Protection reported a significant increase in illegal fentanyl seizures, with 14,700 tons intercepted in 2022, up from 4,800 tons in 2020. In contrast, heroin seizures decreased from 5,800 tons in 2020 to 1,900 tons in 2022. From 2016 to 2020, fentanyl-related drug trafficking offenses skyrocketed by 1,946%, while offenses involving heroin and oxycodone dropped by 33.2% and 47.1%, respectively. Methamphetamine is the only other drug showing an increase in trafficking offenses during this period, rising by 13.9%. The trend of escalating fentanyl offenses continues, with a 435% increase noted between 2018 and 2022.

Nitazenes: New Opioids

| Fentanyl analog | Strength in terms of fentanyl | Strength in terms of morphine |

|---|---|---|

| Protonitazene | 1.07-1.29x greater | 130x greater |

| Isotonitazene | Roughly equal | 2.5 x greater |

and Dangers

Nitazenes are a category of synthetic opioids that, unlike many others, do not share a structural template with fentanyl. This group includes compounds such as etonitazene, isotonitazene, flunitazene, metonitazine, protonitazene, and 5-aminoisotonitazene. Originally developed for pain relief, none of these substances have been approved for medical use in humans.

Remarkably, nitazenes are estimated to be about 10 to 40 times more potent than fentanyl. Over recent years, the number of deaths associated with these drugs has risen, marking them as a growing threat. A significant challenge in addressing this issue is that nitazenes are often not detected in standard toxicology tests, making it difficult to accurately track their impact.

Since 2019, there have been approximately 2,400 incidents involving illicit nitazenes reported to the US National Forensic Laboratory Information System, highlighting the increasing presence and concern surrounding these potent substances.

Xylazine: False Opioid

Xylazine, commonly known as tranq, tranq-dope, sleep-cut, Philly dope, or zombie, is increasingly being used to adulterate street drugs like cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and especially fentanyl. Originally intended for veterinary purposes as an analgesic, sedative, and muscle relaxant, xylazine targets the α-2-adrenergic receptor—similar to the antihypertensive drug clonidine and the muscle relaxant tizanidine. Its effects include central nervous system and respiratory depression, hypotension, hypothermia, and bradycardia, mirroring some opioid effects.

One of the dire consequences of injecting xylazine is the development of severe, necrotic skin ulcerations, which can occur even at sites distant from the injection area. These ulcerations differ from typical infections linked to drug injections. The sedative properties of xylazine allow traffickers to reduce the opioid content in drug mixtures while maintaining similar effects for the user, thereby increasing profitability.

A critical concern with xylazine is that it is not reversed by naloxone, the primary treatment for opioid overdoses, because xylazine is not an opioid. Additionally, xylazine is not detected in routine toxicology screens, making OIRDs involving xylazine particularly perilous and challenging to manage. Moreover, withdrawal symptoms from xylazine cannot be effectively treated with methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone, which are standard treatments for OUD.

Given its profound impacts and the complexity of managing overdoses, xylazine has been officially designated as an emerging threat by the Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy in 2023. Some states, including Ohio and Pennsylvania, are moving to classify xylazine as a controlled substance, even though it is not currently regulated under the Federal US Controlled Substances Act.

Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression

OIRD is a critical condition that often leads to death due to cardiac arrest, which follows respiratory arrest and asphyxia. This sequence of events is triggered by opioids binding to receptors in the central nervous system (CNS). The early signs of OIRD include lethargy, reduced consciousness, and constricted pupils, progressing to more severe symptoms like unconsciousness, seizures, and respiratory distress—characterized by shallow breathing or slow breathing rates, which can lead to a dangerous drop in oxygen levels (hypoxia).

When hypoxia sets in, immediate intervention is crucial. Brain damage can occur within just 3 to 6 minutes of oxygen deprivation, potentially leading to bradycardia (slow heart rate), other heart rhythm problems, and eventually cardiac arrest and death. This creates a critical, narrow window for first responders or caregivers to act to prevent a fatal outcome.

It’s important to note that the toxic effects of opioids occur only when they enter the bloodstream through ingestion, injection, or inhalation. Direct skin contact with these substances does not cause opioid toxicity. This understanding is vital for effectively managing and responding to incidents of opioid overdose, emphasizing the urgency and methods of response that can save lives in cases of OIRD.

Naloxone: A Key Tool in OIRD

Naloxone is an essential medication used to reverse the life-threatening effects of opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD). This includes respiratory depression, sedation, and hypotension. Naloxone works by competing with opioids for binding at µ-, κ-, and δ-opioid receptors in the body, displacing the opioids and quickly reversing their effects.

To be effective, naloxone must reach the opioid receptors promptly and in sufficient concentration to displace opioids from more than 50% of these sites. Treatment of OIRD involves not only administering naloxone but also managing the airway and continuously assessing the person’s oxygenation and ventilation.

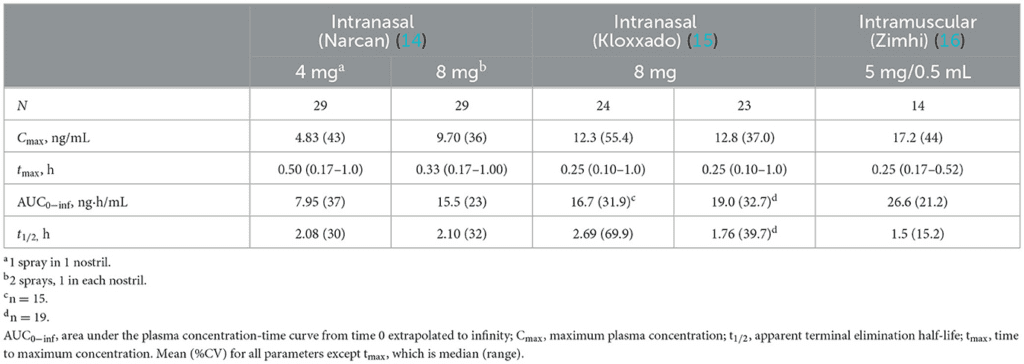

Currently, various naloxone formulations are approved, including nasal sprays, prefilled injection devices, and generic options for intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), or subcutaneous delivery:

- Nasal sprays: Narcan delivers 2 or 4 mg of naloxone hydrochloride with a bioavailability of 44.2%. Kloxxado, another nasal spray, delivers 8 mg with a bioavailability of 41.6%/47.6%.

- Injectable devices: Zimhi, designed similarly to an EpiPen, contains 5 mg of naloxone in a prefilled syringe for IM or subcutaneous administration. It can be administered through clothing into the thigh.

In 2023, the FDA approved 4-mg intranasal naloxone for over-the-counter, non-prescription use, and a 3-mg dose was also recently approved, making it more accessible in efforts to reduce opioid-related deaths.

Naloxone is a critical medication in reversing opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD), with its effectiveness depending on the mode of administration. Intravenous (IV) administration of naloxone acts the fastest, typically within 2 minutes, but requires medical personnel like emergency technicians, paramedics, or nurses. On the other hand, intramuscular (IM) or subcutaneous injections can be administered by minimally trained first responders or even family members, taking effect between 2 and 5 minutes.

Intranasal (IN) administration, while slightly slower than IV, offers a practical solution for rapid deployment in emergencies, especially outside hospital settings. Among the naloxone options, Zimhi, an IM injection, shows a higher maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and a greater area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) than both the 4-mg IN Narcan and 2-mg/2-mL IM generic naloxone doses. This higher bioavailability means Zimhi achieves faster and higher systemic naloxone levels than lower-dose IM/subcutaneous and IN formulations.

Zimhi is not alone in offering high-dose naloxone for rapid administration; Kloxxado nasal spray delivers an 8-mg dose and reaches more than twice the Cmax of a 4-mg Narcan dose in half the time. These differences are significant in treating OIRDs as demonstrated in preclinical studies and pharmacological modeling, which explore the relationship between naloxone plasma levels and µ-opioid receptor occupancy. For instance, higher doses of naloxone administered to rhesus monkeys showed greater receptor blockade, indicative of effective overdose reversal.

Pharmacokinetic models suggest that higher doses of naloxone can more rapidly reduce µ-opioid receptor occupancy by fentanyl, crucial for reversing toxicity. For example, in conditions simulating a mid-range fentanyl exposure, a 2-mg IM dose of naloxone would reduce receptor occupancy to 50% in about 13.54 minutes, compared to just 4 minutes with a 5-mg dose and even faster with a 10-mg dose. This dose-response relationship holds even at higher fentanyl levels, underscoring the importance of dose in naloxone’s effectiveness.

The information underscores the necessity for potent, rapidly-acting naloxone formulations like Zimhi and Kloxxado in managing the critical window during opioid overdose scenarios, enhancing the chances of saving lives.

Synthetic Opioid Overdose Reversal

Nalmefene: A New Player

While much of the focus in opioid overdose treatment is on naloxone, it’s important to also consider nalmefene, a µ-opioid receptor antagonist that offers a new approach to managing OIRD. Approved by the FDA in 2023 as an intranasal (IN) spray under the brand name Opvee by Indivior Inc., each dose delivers 2.7 mg of nalmefene, with additional doses permissible every 2–5 minutes as needed. Nalmefene is not new to the pharmaceutical world; it was initially approved in 1995 as an injectable, though it was later withdrawn in 2008 due to business reasons.

One of the key advantages of nalmefene over naloxone is its longer half-life—approximately 11.4 hours compared to about 2 hours for IN naloxone—which may enhance its efficacy in sustaining opioid reversal. However, this extended action could also lead to prolonged withdrawal symptoms, which some may view as a disadvantage.

High-Dose Naloxone

Recent simulations and feedback from first responders indicate that multiple doses of traditional naloxone formulations (such as 2 mg intramuscular [IM], 4 mg intranasal [IN], and 8 mg IN, the latter equivalent to 4 mg IM) are often necessary to counteract the severe respiratory depression caused by potent opioids like fentanyl. There is a growing recognition that higher doses (e.g., 5 and 10 mg IM) may offer more effective and swifter antagonism of opioids at the µ-opioid receptor level, leading to quicker reversal of toxicity.

Regarding newer synthetic opioids like nitazenes, naloxone remains a potential antidote due to their opioid-like effects. However, their high potency might necessitate higher or more frequent naloxone dosages, similar to those used in treating fentanyl overdoses. For instance, a study involving emergency department admissions found that patients exposed to non-fentanyl synthetic opioids like brorphine and various nitazenes required more naloxone doses, suggesting these substances may be more potent than fentanyl.

Xylazine, an α2-adrenergic receptor agonist often mixed with opioids, complicates the clinical picture as it does not respond to naloxone, which targets opioid receptors. Thus, while naloxone can reverse the opioid effects in a xylazine-adulterated OIRD, it does not affect the depressive effects caused by xylazine itself. This situation underscores the necessity for hospitalization, where treatment can include IV fluids, intubation, and possibly cardiac interventions.

Given the complexity of these cases, especially when the presence of substances like xylazine may not be initially apparent, it is crucial for all OIRD patients to be transported to a hospital for comprehensive evaluation and appropriate continued care.

Challenges in Opioid Overdose Treatment

The introduction of high-dose naloxone formulations has been generally positive, enhancing the capabilities of first responders in emergency situations involving opioids. However, there are ongoing debates about their necessity. Critics argue that existing data on the number of naloxone doses needed during OIRD interventions are inconclusive and complicated by factors like the presence of sedating drugs and adulterants, questioning whether standard doses are indeed insufficient.

In a 2022 study, the public’s perception of naloxone efficacy, especially after administering the drug, indicated a strong preference for higher doses. Most respondents (87%) felt more confident using an 8-mg IN naloxone spray compared to a 4-mg dose, with 76% preferring to carry the higher dose. This preference was largely driven by beliefs that the higher dose could act faster and more effectively, particularly in communities affected by fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

When using naloxone to reverse OIRD, certain adverse effects can occur, particularly in individuals with physical dependence on opioids. Notably, while symptoms such as vomiting and aspiration present risks, they are rarely fatal and are considered less critical than addressing the life-threatening effects of an overdose like respiratory depression, unconsciousness, bradycardia, and hypothermia—all of which are reversible with naloxone.

Rare but serious condition is naloxone-induced non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. This condition may arise from a surge in catecholamines triggered by naloxone, leading to blood volume shifts and increased pulmonary permeability. Although there’s concern that higher doses of naloxone might elevate this risk, studies show mixed results. One study indicated a higher incidence of pulmonary complications with doses above 4.4 mg, while another found no significant correlation between naloxone dose and the occurrence of pulmonary issues or extended hospital stays.

The evolving landscape of opioid abuse, particularly with potent substances like fentanyl and its analogs, often necessitates multiple, higher doses of naloxone. These substances’ potency can mean that a single administration of naloxone may not suffice due to its relatively short half-life, which might require repeated dosing to maintain effectiveness as opioid levels remain high in the body.

Despite the need for higher-dose options, there’s a concern that their availability might overshadow lower-dose formulations, potentially reducing their use. It’s crucial to remember that any naloxone, regardless of the dose, is beneficial. In the context of the ongoing opioid crisis, the adage that “perfect should not be the enemy of good” holds particularly true. The priority should be to enhance accessibility to all forms of naloxone, ensuring that those experiencing an overdose have the best possible chance at recovery. This approach underscores the importance of naloxone as a lifesaving tool, irrespective of the dosage.

Expanding Education in Naloxone Use

Handling Injectable Naloxone: A prevalent concern with naloxone, particularly the injectable type like Zimhi, is the use of needles. This can be daunting for first responders and caregivers, despite its critical role in emergency situations involving opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD). While individuals with a history of substance use involving syringes may not find this concerning, others might worry about the complexity of using a traditional syringe. However, devices like Zimhi are designed for ease of use, featuring a needle shield to prevent injuries post-use, which addresses one of the main fears surrounding needle sticks. Education and hands-on demonstrations can significantly help in alleviating these concerns, ensuring that Zimhi is as approachable and straightforward to use as nasal sprays like Kloxxado and Narcan.

Real-world Education and Stigma Challenges: Despite widespread awareness of the opioid crisis, there remains a significant gap in public understanding of naloxone and its application. The stigma surrounding OUD often deters families from obtaining naloxone, for fear of judgment or repercussions regarding insurance or employment. Moreover, the presence of law enforcement at overdose scenes can discourage calls for help due to fears of legal consequences, despite Good Samaritan laws designed to protect those seeking medical aid in such emergencies.

Education plays a crucial role not only in demonstrating how to use naloxone but also in understanding when and how to seek it. Emergency calls should be made immediately before or after administering naloxone, as the patient may require further medical intervention due to the short half-life of naloxone and the long-lasting effects of potent opioids like fentanyl.

Guidelines and Accessibility: The CDC recommends that individuals at risk of an opioid overdose be provided with a naloxone prescription along with their opioid prescription. Risk factors include high opioid dosages, concurrent prescriptions like benzodiazepines, and certain medical conditions. Despite increased naloxone availability over the past two decades, distribution at community pharmacies remains relatively low, underscoring the need for broader access and education.

Expanding naloxone distribution is critical, not only as a lifesaving measure but also as a potential gateway to treatment. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) options like buprenorphine and methadone are vital components of OUD treatment, and naloxone can serve as a crucial first step on the path to recovery. Increasingly, naloxone is available without a prescription, through pharmacies, community programs, and non-profits, enhancing access.

Data and Advocacy: Real-time data collection on OIRDs through platforms like the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODmap) provides invaluable information to first responders and public health officials. However, the quality of the data and the participation rate among states can vary, sometimes limiting the effectiveness of response strategies.

Education and advocacy are essential not only for promoting naloxone use but also for integrating it into broader health care strategies that include MAT. With recent changes in prescribing regulations for substances like buprenorphine, more medical professionals, including pharmacists, can engage in this critical aspect of public health.

Moving forward, it is crucial that all FDA-approved naloxone products, whether intranasal or injectable, are made widely available to combat the opioid epidemic effectively. This approach ensures that naloxone remains a cornerstone of emergency responses to OIRD, ultimately saving lives and facilitating long-term recovery solutions.

Conclusion

The emergence of new synthetic opioids represents a significant challenge in the ongoing battle against the opioid epidemic. These substances, often more potent and dangerous than their predecessors, necessitate a multi-faceted approach to drug policy, healthcare response, and public education. As the landscape of opioid misuse continues to evolve, it is critical that our strategies adapt accordingly.

Public education campaigns are essential to raise awareness about the risks of synthetic opioids and to disseminate information on how to respond to overdoses. These campaigns should aim to reduce stigma and promote a more compassionate approach to those affected by OUD.

Regulatory bodies must enhance surveillance, stricter import controls and more rigorous monitoring of chemical precursors. Healthcare systems need to be equipped with the latest in treatment and overdose-reversal technologies, such as advanced formulations of naloxone, to respond effectively to the unique challenges posed by these potent drugs.

Furthermore, research into the effects and treatments of synthetic opioid exposure must be a priority to stay ahead of these substances as they develop. Only through a comprehensive and informed approach can we hope to mitigate the profound impact of these drugs on individuals, families, and communities.

In conclusion, as we face this new wave of synthetic opioids, our response must be robust, adaptive, and grounded in a deep understanding of the science and sociology of addiction. The stakes are high, and our actions now will shape the health outcomes of generations to come.